In my last post I talked about some tricks for fitting more sprites into your spritesheet, but I didn’t go into a lot of context about what that even means. In this post, I want to cover what a spritesheet is and why you might use one. I’ll start by explaining a bit about how game engines work.

How do game engines work with images?

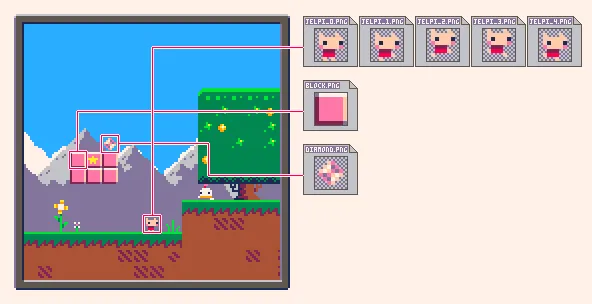

Here’s a frame of a game. It’s made up of a bunch of smaller images, called sprites in gamedev lingo, that get layered together to produce the final image.

There are a few different ways game engines could handle drawing a frame like this. One way is to load a bunch of separate image files — one for each sprite — and draw each one in its corresponding position in the frame. Indeed, many game engines support this workflow, and if I were inventing a game engine from first-principles, this is probably what I’d come up with.

A frame drawn from individual files

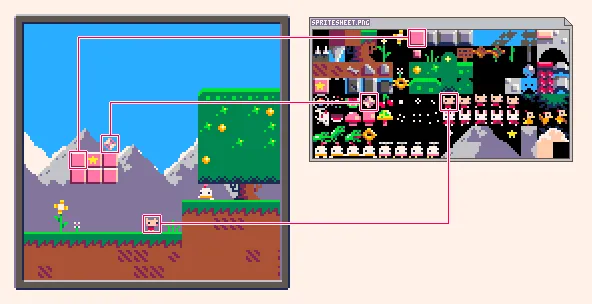

But there’s another way! You could combine all of your sprites into a single image, called a spritesheet, then draw a frame by clipping out rectangular pieces of it and pasting them into place.

A frame drawn from a single spritesheet

So, there you have it. A spritesheet is an image that contains a collection of individual sprites!

But that raises an important question… why?

Why use spritesheets?

Depending on your game engine or target platform, the answer could be “that’s just how it works”. For example, PICO-8 doesn’t support loading and drawing separate image files. There’s only one spritesheet that has to contain everything, and its size is limited to 128x128 pixels (this is why Spooky Stylin’ needed to use some clever Spritesheet Tricks). A lot of “retro” consoles had similar constraints as well due to limitations of the technology.

But spritesheets aren’t just a retro thing. A lot of modern games still use spritesheets or texture atlases, a similar technique of combining multiple 3d-model textures into one image. Why is that?

One reason is performance. It can be much more efficient to load a batch of images all in one go, rather than one at a time, both in terms of getting the images from your filesystem into your game, and in terms of getting the images from your game onto the graphics card where they’ll be ready to be drawn to the screen. That is to say, spritesheets are a useful optimization technique.

Another reason is that, depending on your workflow, spritesheets can also be more convenient to work with. A lot of animation programs have a way to export frames as a spritesheet — some can also export useful metadata about how many frames there are, which frame each animation starts on, etc. This means you can export a single file instead of a bunch of individual frames.

It’s not all-or-nothing

So far, I’ve talked about two extremes—one spritesheet for everything, or one file per sprite—but in practice, that’s quite rare. Lots of games use an approach that’s somewhere in between. For example, each character could be on a separate spritesheet, the tileset used for the level could be another spritesheet, and rarely used or one-off sprites could be loaded as individual images. Splitting up sprites like this is a good middle-ground. That way, your game engine has to load fewer images in total compared to the one-image-per-sprite approach, and you can also keep your assets organized more easily compared to the one-spritesheet-for-all approach.